CMSC

-0.1800

"Blade Runner" and "Chariots of Fire" composer Vangelis, the electronic music pioneer and sole Greek to win an Academy Award for best original score, died late Tuesday aged 79.

The reclusive, mostly self-taught keyboard wizard was a lifelong experimenter, switching from psychedelic rock and synth to ethnic music and jazz.

In a career spanning over five decades, Vangelis drew on space exploration, wildlife, futuristic architecture, the New Testament and the 1968 French student riots for inspiration.

His Oscar-winning main theme for "Chariots" beat John Williams' score for the first Indiana Jones film in 1982. It reached the top of the US billboard chart and was an enduring hit in Britain, where it was used during the London 2012 Olympics medal presentation ceremonies.

True to form, Vangelis was fast asleep in London when the result was announced on March 29, 1982 -- his 39th birthday.

"I'd been out late celebrating," he later told People magazine.

His work on over a dozen soundtracks included Costa-Gavras' "Missing", "Antarctica", "The Bounty", "1492: Conquest of Paradise", Roman Polanski's "Bitter Moon" and the Oliver Stone epic "Alexander".

Vangelis readily admitted to the Los Angeles Times in 1986 that "half of the films I see don't need music. It sounds like something stuffed in."

He also wrote music for theatre and ballet, as well as the anthem of the 2002 FIFA World Cup.

- Child prodigy -

Born Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou in the central Greek coastal town of Agria, near Volos, Vangelis was a child prodigy, performing his first piano concert at the age of six, despite never having taken formal lessons.

"I've never studied music," he told Greek magazine Periodiko in 1988, in which he also bemoaned growing "exploitation" by studios and the media.

"At one time there was a craziness... now it's a job."

"You might sell a million records while feeling like a failure. Or you might not sell anything feeling very happy," he said.

After studying painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts, Vangelis joined popular Greek rock group The Forminx. But success was cut short in 1967 by the arrival of a military junta that clamped down on freedom of expression.

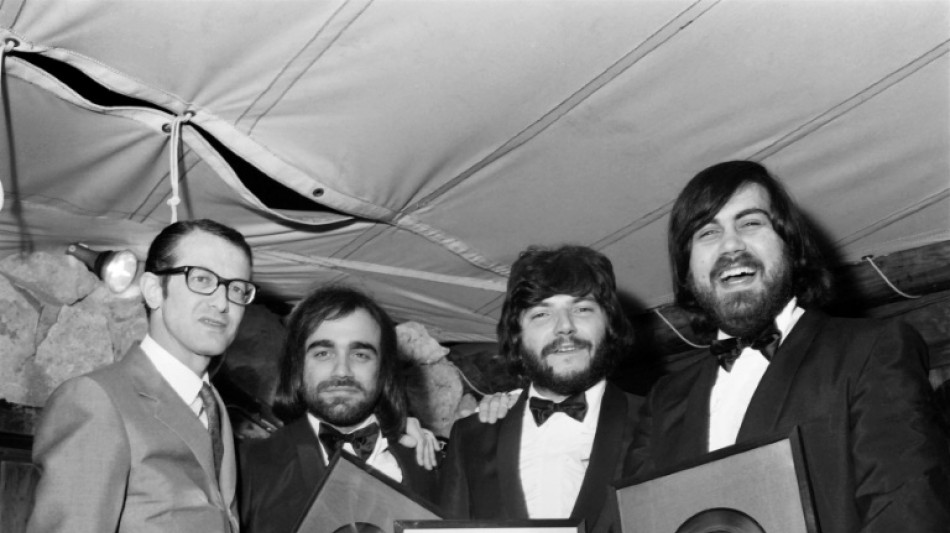

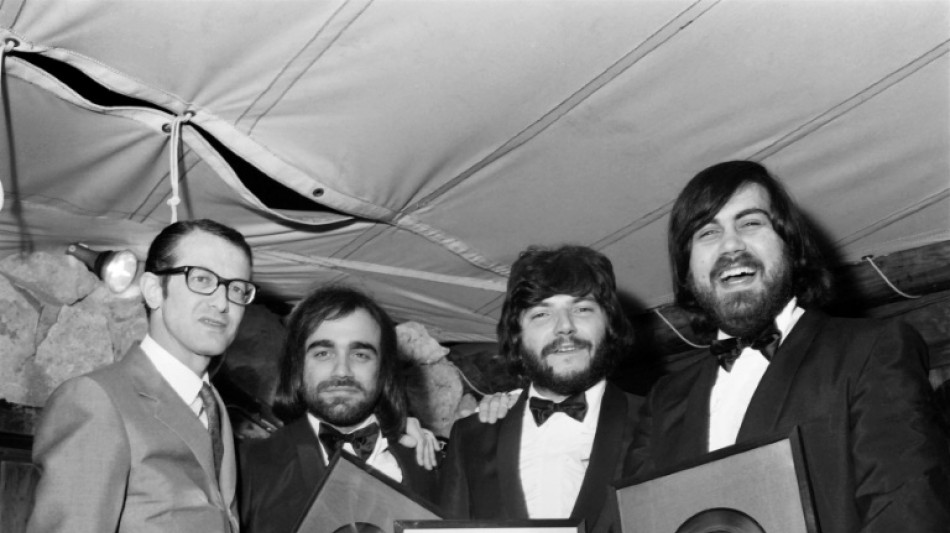

Trying to get to England, he found himself stuck in Paris during the 1968 student movement, and joined fellow Greek expatriates Demis Roussos and Lucas Sideras in forming progressive rock group Aphrodite's Child.

The group achieved cult status, selling millions of records with hits such as "Rain and Tears" before disbanding in 1972. Vangelis and Roussos both moved on to successful solo careers.

Relocating to London in 1974, Vangelis created Nemo Studios, the "sound laboratory" that produced most of his solo albums for over a decade.

But he valued his independence over record sales.

- 'Success is treacherous' -

"Success is sweet and treacherous," the lion-maned composer told the Observer in 2012. "Instead of being able to move forward freely and do what you really wish, you find yourself stuck and obliged to repeat yourself."

In a 2019 interview with the Los Angeles Times, the composer said he saw parallels with the dystopian world depicted in "Blade Runner".

"When I saw some footage, I understood that this is the future. Not a nice future, of course. But this is where we’re going," he said.

Vangelis, who had a minor planet named after him in 1995, had a fascination with space from an early age.

"Each planet sings," he told the LA Times in 2019.

In 1980, he contributed music to Carl Sagan's award-winning science documentary Cosmos. He wrote music for NASA's 2001 Mars Odyssey and 2011 Juno Jupiter missions, and a Grammy-nominated album inspired by the Rosetta space probe mission in 2016.

In 2018, he composed a piece for the funeral of Stephen Hawking that included the late professor's words, and was broadcast into space by the European Space Agency.

Vangelis has been a recipient of the Max Steiner film music award, France's Legion d'Honneur, NASA's Public Service Medal and Greece's top honour, the Order of the Phoenix.

In later years, Vangelis moved between homes in Paris, London and Athens, carefully guarding his privacy. Little is known of his personal life.

"I don't give interviews, because I have to try to say things that I don’t need to say," he told the LA Times in 2019.

"The only thing I need to do is just to make music."

A.Ferraro--NZN