RBGPF

61.8400

It is one of the most unforgettable opening scenes to play at the Venice Film Festival: a baby pushed back into its mother because, he informs the doctor, who would want to live in this screwed-up world?

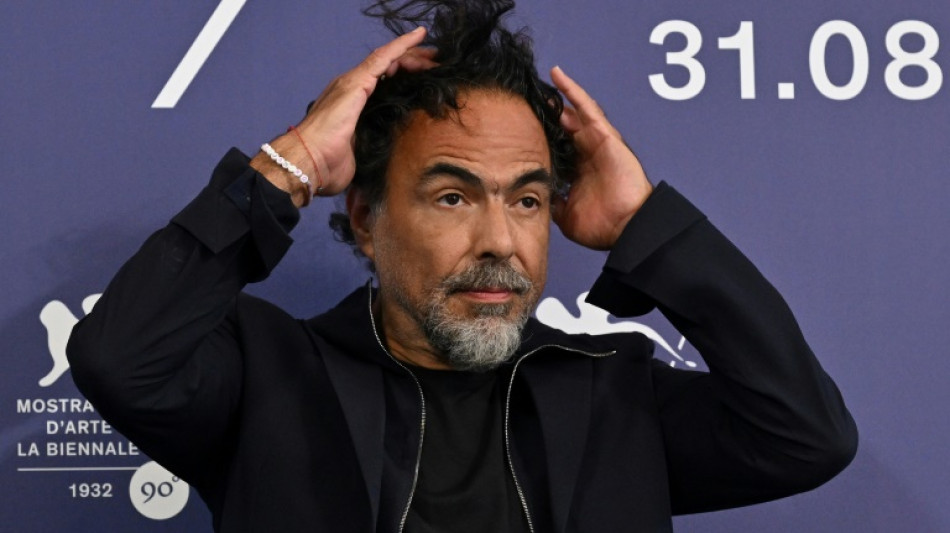

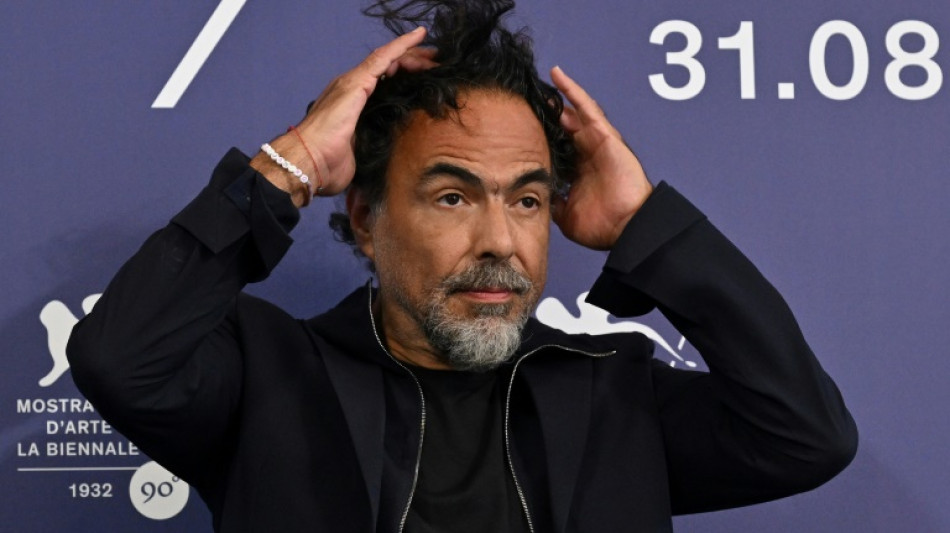

That was the fantastical and audacious opening that marked Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu's return to the big screen on Thursday, after a seven-year hiatus following back-to-back Oscars.

"BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths" is a deeply personal film that brings the director back to his home country of Mexico following two Best Director Academy Awards in 2015 and 2016 for "Birdman" and "The Revenant".

The film "wasn't developed by my mind, but by my heart", he told journalists, calling the nearly three-hour Netflix film an "emotional reinterpretation of a memory".

The film centres on journalist played by Daniel Gimenez Cacho about to accept a major prize in America -- success that sparks an existential, mid-life crisis and increasingly fuzzy lines between reality and memory.

"Every time, I'm less interested in reality in film," Inarritu said, calling it "limbo".

Featuring sweeping dreamscapes involving the parched Mexican desert, a post-apocalyptic Mexico City and the ruins of an Aztec citadel, the film is anchored by real-world relationships, between fathers and sons, husbands and wives, or even people and their homelands.

- Cortez and criminals -

We see Mexico's pained history in dreams -- scores of natives massacred by Cortes' 16th century invaders, or Mexican patriots desperately fending off US troops in the Mexican-American war -- as well as today's reality in the form of migrants making perilous attempts to cross the US border.

In one scene, heaps of plantains pile up in a deserted Mexico City street, as "desaparecedos" -- the tens of thousands of disappeared Mexicans abducted by criminal gangs or the state -- fall from the sky.

Racial and social inequalities within Mexican society are touched upon, but with a lighter touch than seen in "New Order" by Michel Franco, a violent, searing indictment of the gap between Mexico's rich and poor that won Venice's Grand Jury prize in 2020.

"Mexico is not a country, it's a mental state for me," said Inarritu, who said he wanted to examine the "longing" for one's country after having himself left Mexico for Los Angeles over two decades ago.

"But when you get far away from that place and when time goes by, this state of mind dissolves and changes."

S.Scheidegger--NZN